July, 2020

An exploration of the garment industry through the historical lens

8 minutes read

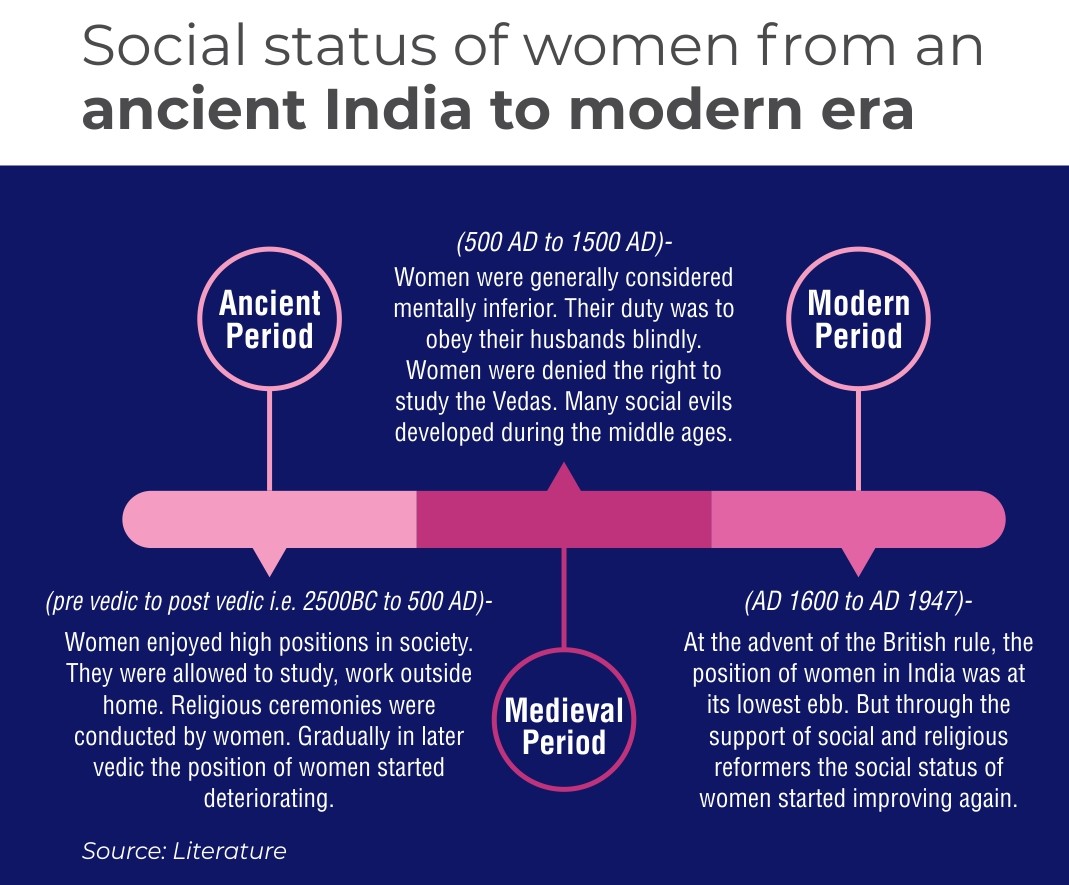

The history of Indian textiles is as old as human civilization. According to archaeologists, evidence of weaving has been found from Indus valley and Mohenjo-Daro civilization dated back to 3000 BC. Weaving practices have also been referred to in the oldest Sanskrit composition of Rigveda . From medieval to modern history this sector dominated the trade and commerce of our country. Currently it contributes to 2% of GDP and provides employment to 45 million of people directly and 60 million people indirectly in which women comprise the major half of the informal workforce. From the pre-vedic era to that of post-independence, women played a crucial role in shaping the Garment Industry of India. As the industry has been here for a while, how has it shaped society? Has it treated women the same as men throughout? Did we have our fall from grace there with time? Is the industry inherently marred with systemic problems or are the political conditions? This article aims to explore all this through a historical lens.

While garment making started off as a profession of respect, the people wearing the clothes and making them face significant ups and downs. According to the Arthashastra, women were not permitted to engage in any other occupation, leaving them only with weaving, spinning, and other art and crafts based from their homes. Gradually, weaving became the occupation which was looked down upon as mostly lower caste women started involving themselves in this profession. Additionally, women started facing a lot of exploitation during the colonisation of India in this industry which is still prevalent to this day through low wages, job insecurity, gender-based discrimination, sexual harassment, unsanitary working conditions at factories etc.

Pre Vedic and Vedic Times (2500 BC- 700AD)

The ancient Indian textile industry appeared to be dominated by women. Evidence of clothing has been found from impressions made into clay or iconography during Indus valley civilization. They depicted the men wearing a long cloth wrapped over their waist and fastened it at the back (just like a close clinging dhoti). Turbans were also customary in some communities as shown by some of the male figurines. Evidence also shows that there was a tradition of wearing a long robe over the left shoulder in higher class society to portray their opulence. The normal attire of the women at that time was a meagre skirt up to knee length leaving the waist bare. Accessories of jewelry and ornaments were common to both males and females.

During that time in the Aryan society men and women would both weave and so the women were again given a position of respect in society. In the Sama Veda and Rig Veda we find mentions of weaving with high praises for example following chants in the Vedas,

Om Ja Akrintanayabayan Ja atannata

Jasccha Debbya Antanvitohatatashthya i

Tashtawa Debbya Jarosa Sangbay –

Nataushmateedang Paridhatswa basow : 11~11

Om Pari Datwa Datwa Basosaina; sataushe; krinnuto Dirghomaue,

Satancho Jibo Sarodo : Saccha

Bosuni Charjye Bivrijasi Jiban II

(-Iti Ahnik Krityamadhritya: Beda Mantram)l

It means the “ones who have made the yarns, woven the cloth, made the thread and completed the border they are the adorable ladies who made one wear clothes till old age. O the lucky one, do wear the cloth.”

As both genders engaged in weaving, it was considered to be a ‘higher’ occupation in society and women were also respected for this profession. Thus, occupational respect was based on if men deemed it to be so. Generally, the women belonging to higher castes were involved in this work as mentioned in the ancient literary sources. The clothing system was also related to the social and economic status of the person. The upper classes of the society wore fine muslin garments and silk fabrics while the common classes wore garments made up of locally made fabrics. For instance, women from rich families wore clothes (sari specifically) made up of silk from China, but the common women wore sari made up of cotton or local fabrics. Hence, caste and class were both entwined in one’s garments.

Medieval period (700 AD to 1550 AD)

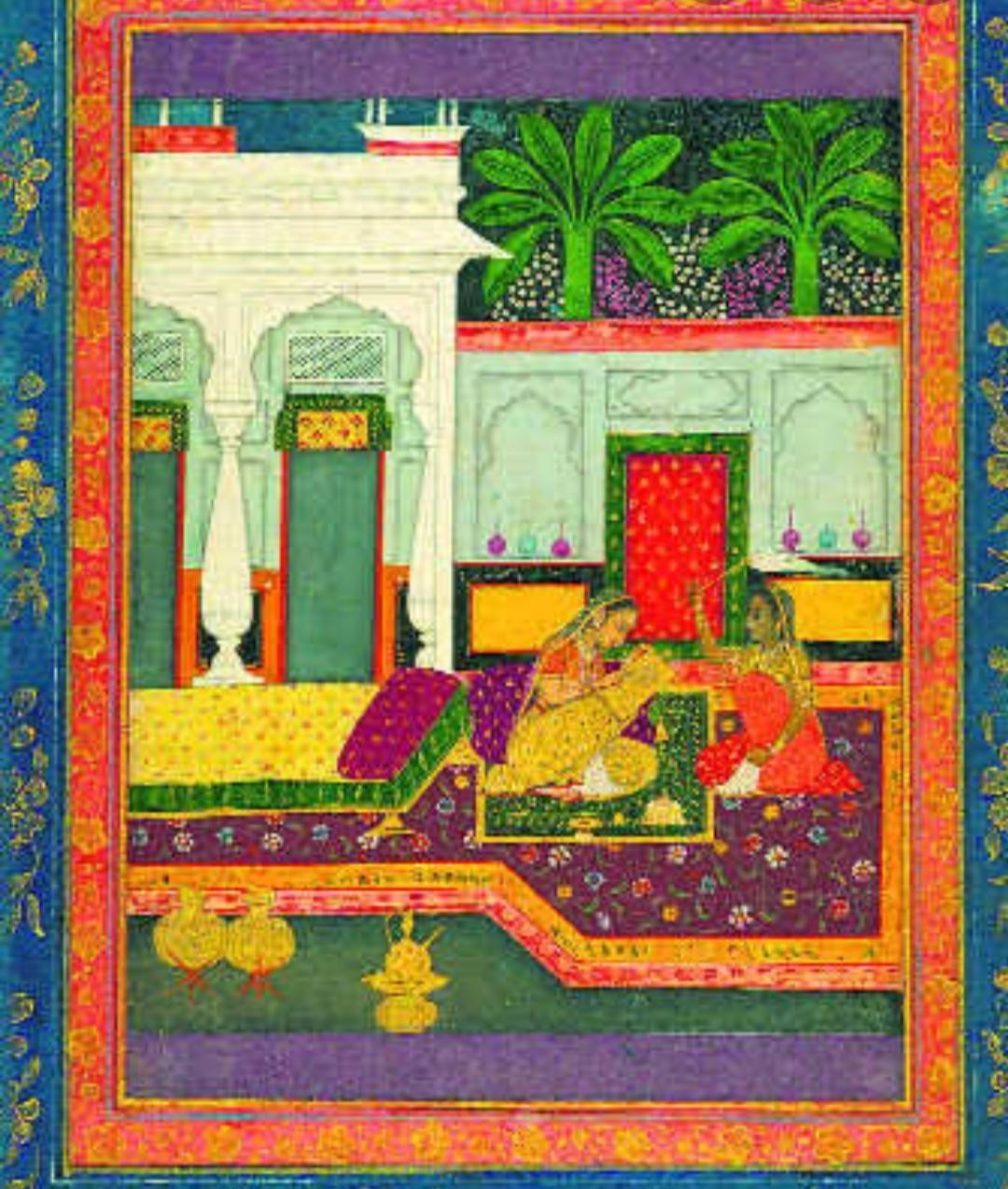

Have you heard about “Meena bazaar” and ” kinari bazar” during the time of Mughal emperor the great Akbar? It was essentially a market in which women usually put up stalls of different kinds of handmade clothes and handicrafts. During this period, the royal women of the harem like Jodha Bai , Nurjahan etc. gave impetus to the garment industry through endorsing fabric works such as the muslin of Dacca, cotton of Benaras in India which was traded to different countries .Women often participated in vital cottage industries, such as brewing, baking and manufacturing textiles. The most common symbol of the peasant woman was the distaff – a tool used for spinning flax and wool. References given in ‘Ain-i-akbari’ of Abul Fazal that women were the main spinners and they usually worked in their homes and also in the karkhanas which were the main textile producing industries of this period. They received their wages according to the home-based products they sold in the market and in karkhanas according to their skills and their contribution. Common women usually wore cotton fabrics clothes and high-class women used to wear muslin or fine quality clothes. Again, the clothing style varied according to hierarchical positions in society. So far, while caste and class affected the garments worn, history was about to take a turn which would affect the people making these garments as well.

Women working in “Harem”

Modern period – Colonization of India (1550 AD to 1947AD)

Next came the classic tale of greed wearing the garb of colonization. A vibrant nation flourishes in global trade and culture, catches the eye of an empire that promptly swoops in, takes over the nation, holds them in bondage for centuries, until a grassroots movement rises to remove the imperialists and claim what is rightfully theirs. It’s the story of India’s independence.

What often gets underreported is the extent to which the British destroyed India’s local industries to assert its dominance, the economics was overshadowed by the politics. For instance, India was manufacturing 25% of the world’s textiles in the 17th century, and that this share plummeted to just 2% at the end of British colonialism in 1947 (Das 2002). This occurred due to the Industrial Revolution in the 18th century in Europe, which affected the whole economy of India.

Before the Industrial Revolution, hand spinning had been widespread female employment. It could take as many as ten spinners to provide one hand-loom weaver with yarn, and men did not spin, so most of the workers in the textile industry were women. The new textile machines of the Industrial Revolution changed that. Wages for hand-spinning fell, and many rural women who had previously worked in the industry found themselves unemployed. In a few locations, new cottage industries such as straw-plaiting and lace-making grew and took the place of spinning, but in other locations, women remained unemployed.

The advent of new machinery changed the gender division of labor in textile production. Before the Industrial Revolution, women spun yarn using a spinning wheel (or occasionally a distaff and spindle). Men didn’t spin, and this division of labor was logical because women were trained to have more dexterity than men, and because men’s greater strength made them more valuable in other occupations. In contrast to spinning, handloom weaving was done by both sexes, but men outnumbered women. Men monopolized highly skilled preparation and finishing processes such as wool combing and cloth-dressing. With mechanization, the gender division of labor changed, and men had the power in the historically ‘female-dominated’ industry.

A defining feature of the Industrial Revolution was the rise of factories, particularly textile factories. Work moved out of the home and into the factories. For some, the Industrial Revolution provided independent wages, mobility and a better standard of living. For the majority, however, factory work in the early years of the 19th century resulted in a life of hardship. Women were not valued the same as men in the workplace, and were often paid much less than men. For example, while male British industrial workers were often paid about 10 shillings per week, women were paid half that. Along with poor pay, women were also subjected to horrible conditions in the workplace as they were sexually exploited and abused by their owners, they were also denied overtime pay or pay for going above and beyond what their targets were. Working conditions were often unsanitary and the work dangerous. They were also not provided with proper meals which resulted in poor health and malnutrition. Women at this time did not enjoy maternity benefits due to which many women lost their jobs. Their education suffered due to the demand for work. The quality of life suffered as women were faced with the added burden of factory work followed by domestic chores and child care. Men assumed supervisory roles over women and received higher wages. Unsupervised young women away from home-generated societal fears over their fate. As a result of the need for wages in the growing cash economy, families became dependent on the wages of women and children. There was some worker opposition to proposals that child and female labor should be abolished from certain jobs.

To this day exploitation persists in the industry. The handloom industry is one of the oldest cottage industries in India. Women have played a significant role in shaping the garment industry. Without the participation of women, it would not have been what it is today.

Given that the Ministry for Textiles is being led by a woman, it’s only natural that the ministry has schemes specifically for the upliftment of women employed in the sector. About 77 percent of workers employed in the handloom sector are women. The Ministry of Textiles launched four exclusive schemes for them – National Handloom Development Programme, Handloom Weavers’ Comprehensive Welfare Scheme, Yarn Supply Scheme, and Comprehensive Handloom Cluster Development Scheme. Women belonging to the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes and below poverty line (BPL) families can utilize a 100 percent subsidy for construction of work sheds under the National Handloom Development Programme.

But still there are certain lacunae in the formulation of policies and its implementations. These challenges must be resolved through effective and bold steps. It is now time to deepen and expand that work to better address the specific needs of women workers in the global value chain in collaboration with suppliers, NGOs, international development agencies, and governments. The garment sector can influence policy change and drive industry-wide progress by sharing knowledge and expertise, and supporting policies proven to advance women’s empowerment and gender equality. These policies can address challenges such as security of job, sexual harassment at the workplace, formalization of work, protection from violence sanitation and hygiene and equal pay for equal work. This could be accomplished through a variety of approaches, including a collective manifesto, joint statement, or public principles.

“We need women at all levels, including the top, to change the dynamic, reshape the conversation, to make sure women’s voices are heard and heeded, not overlooked and ignored.” – Sheryl Sandberg

As the largest democracy of the world, who have also committed to fulfilling the Sustainable development goals numbered 1, (No Poverty); 5 (Gender Equality); 8 (Decent Work), we can’t ignore the rights of these women, they must be protected and more importantly empowered. When it comes to the three basic needs of survival, one instantly thinks of roti kapda and makaan. As these women fulfill the basic need of our kapda, it is fundamental that people working to clothe us feel empowered.

References

- International Journal Of Trend In Scientific Research And Development: Golden Era of Indian Textile Industry, 2019

- Cottage Industry Clusters in India, 2014

- Cotton Textile Industry in India: Production, Growth and Problems, 2016

- Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad: Competitiveness of Indian Textiles and Garment Industry: Some perspective, A Presentation, 2004

- Essay on the Problems of the Cottage Industry in India, 2020

- 5 Ways Imperial Britain Crippled Indian Handlooms. 2019

- Arts And Social Sciences Journal: Garment Export Industry of India – A Comparison of Pre and Post Liberalization Performance, 2015

- Research In Educational Policy And Management: Educational, Social and Economic Status of Women in Textile Industry in India, 2019

- Journal Of Applied And Advanced Research: Safety Issues of Female Workers of Garment Industry in Gazipur District, Bangladesh, 2017

- Participation and role of women in Cotton weaving industry of Shantipur and Phulia – Chapter (V)

- Social Scientist: New Opportunities on Old Terms – The Garment Industry in India, 1987

- Siddharth Kara Blum Center for Developing Economies (UCB): Tainted Garments the Exploitation of Women and Girls in India’s Home-based Garment Sector, 2019

- The Social ION: Status of women in ancient India, 2018

- Texmin Official Website of Ministry of Textiles Govt. Of India, 2003

Image credits

- W.668, 1585 CE, Oriental, Album of Persian and Indian calligraphy and paintings, (Iran or India)

- Photo12/Universal Images Group via Getty Images, 1943, Photograph taken during war-time India of young female workers in a booming Bombay textile mill

[…] time immemorial, women have predominantly assumed the role of caregivers. This led to the emergence of certain […]