August, 2021

This article deals with the repercussions of the debt cycle among women work from low income households and solutions to tackle the same

7 minutes read

Poverty reduction efforts have been ubiquitous since the turn of the century; especially so after both the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), both blueprints for all countries to end deprivation of basic needs and ensure better lives for all, placed its eradication as the foremost goal of global society. Yet, poverty remains recalcitrant, with many Asian and Sub-Saharan nations mired in it. Closer home, poverty has a long and arduous history in India, hallmarked by low incomes and savings as well as inaccessible or prohibitive credit, investment and healthcare.

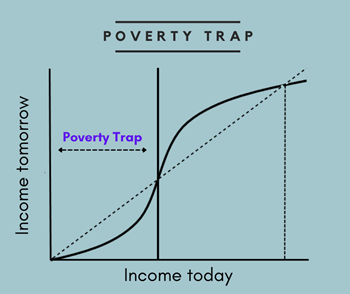

It is a sobering truth but many households (especially rural) don’t just face high levels of debt, but also have to cope with low and irregular incomes without the aid of financial instruments to tide this volatility. Compounded by inadequate saving mechanisms and crumbling healthcare infrastructure, families find themselves on the slippery slope that is a poverty trap.

While literature on the economics of the poor has evolved over the last century, there have been some worrying trends in recent years. Take the Permanent Income Hypothesis. It suggests that in the event of income and economic shocks, if households feel optimistic about their outlook, they would choose to maintain their consumption levels even if their income declines.

However, 46% of households that previously treated borrowing as a last resort, now meet their basic, essential expenses through borrowing, according to a study in 2020 by Home Credit India. This is a drastic change from when families borrowed for want of consumer durables. This has only been exacerbated by the fact that medical expenses have been increasingly driving families to the precipice of poverty.

This is disconcerting for many reasons, not the least of which is that the dearth of assets to offer up for collateral and the reluctance of banks to lend to such clients force low-income families to have to resort to borrowing from informal sources like moneylenders, who charge exorbitant interest rates.

Inevitably, they grapple with the surmounting debt, which further impedes the chance to break free of the vicious circle of poverty. To cope with the repayments, they may even borrow more, which in no way ameliorates their situation.

However, less poor households do not find themselves as encumbered since they are less likely to resort to informal sources, and even when they do, moneylenders charge higher rates for the poor than the less poor. On average, for every additional hectare of land owned, the rate of interest charged by an informal source drops by 0.4 %. Thus, this disparity leaves low-income families particularly at risk to not only find formal credit inaccessible, but even informal credit to be expensive.

Poor saving and high interest rate borrowing practices can often leave low-income households so entrenched that not only are they unable to get out of a debt trap, but even after receiving assistance or grants to rid themselves of debt, will find themselves falling back into borrowing in the near future. And this problem isn’t endemic to just developing nations. Case in point, payday loans in the US have pulled many at risk poor families into an unbreakable cycle of endless debt.

Prompted by high household debt, the Indian government has repeatedly announced a slew of loan waivers over the years. Beneficial as debt relief may be to the individual, its merit may be undercut by the fact that it could weaken prudence in taking on debt and resolve to repay, aside from the fact that such moves were usually politically motivated. Banks too become increasingly wary when it comes to lending to low-income households, perpetuating the reliance on informal sources like moneylenders.

Clearly, borrowing implicitly comes with a high risk for these households, so surely they could instead save more and reduce their borrowing, given the high return to savings, right? On the contrary, despite existing saving mechanisms, low-income households fail to save adequately. A predominant reason for this is their innate high marginal propensity to consume. A study found that food itself represented 36-79% of the budgets of extremely poor rural households and parallely 53-74% in urban households. Perversely, among the very poor in Maharashtra, expenditure on food isn’t intended to maximize their calorie intake; counter-intuitively, when they can spend more on food, they consume food that is more expensive and tastes better, instead of getting more calories.

Inadequate saving is underpinned by poor outlook – poor households find saving and planning for investments such as consumer durables, higher education, etc, an expensive ordeal and thus less attractive; the income in hand today could be better spent for more immediate needs. Saving is a tedious task for anyone, but poor households are predisposed to be discouraged from doing so due to the absence of effective mechanisms to save. For instance, salaried persons save better due to provident funds and pension plans in place. Thus, higher incomes make the decisions to save easier.

Since today’s savings forms the basis for tomorrow’s wealth, poor households save less and thus have lesser resources in the future as they consume more. Conversely, higher-income households save a greater proportion of their current resources, leading to higher levels of wealth in the future. Predictably, the poor grow poorer, the rich richer.

Women, Informality and Gendered Debt

In developing nations like India, for most women belonging to low income households, the way to be a part of the labour force is via the informal sector. The formal sector brings with it multiple entry barriers, which women of low income households find difficult to break. Thus, women of all ages constitute a larger share of the workforce in informal sectors as domestic help, construction workers.

Bearing the onus of reproductive labour, women, especially from low-income households, will often find themselves settling for part-time work. The characteristics of part time work, essentially for women, entail that they tend to be under-employed, willing to work for longer, but resigned to lower earnings.

Despite the low wages, income from women’s informal employment significantly contributes to poverty reduction. However, what invariably blocks them from permanently lifting themselves out of poverty is the debt/credit dyad that traps them in the cycle of indebtment.

Women own 20% of all enterprises in India, and yet evidence suggests that women face unequal access to loans and grants as opposed to men. These inequities become far more pronounced when gender converges with other identities like caste, religion, disability, etc; widening both gender disparities and disparities between women themselves.

Women, particularly from rural and poor families, find it especially difficult to source funds from formal lenders and thus have little to no access to large, long-term, planned credit. And when they are available, it is on the basis of many conditions that most women may not be able to fulfill – considerable social status, a good network of contacts, assets for collateral. Apart from other socio-economic qualifications, they may also need to travel far from their homes to even meet the lender.

Thus, such exclusion compels women to have to borrow so-called instant loans from informal lenders within their community, which implicitly comes with many risks and may even leave them susceptible to harassment and violence from lenders. These instant loans are also highly stigmatized and considered demeaning, since they are often taken to make ends meet. These lenders are often exploitative and coerce women to comply with their demands, with threats of violence and public shaming. And by the very fact that these loans are used to run households, husbands will often not share responsibility or even intervene on their behalf.

When it comes to decisions about household finance, plans of strategic investment and spending are made by husbands, but the management of everyday expenses are promptly handed off to the women. Studies have shown that males in a household take decisions on credit more often and accumulate debt to pay off larger household expenditures on assets like appliances; even using their partner’s names when they can’t take on more debt after they have been blacklisted.

Thus, productive investments by and large remain the prerogative of the males. Debt, or survival debt, is taken on by women to cope with daily expenses. In poor and marginalized families, women hold the highest share of debt, since they take out credit more frequently to smooth over consumption and repay other loans. Consequently, debt taken on by women remains just that; it rarely translates into productive investment that improves their outlook and instead traps them in a never-ending cycle.

However, perversely counter-intuitive as it may seem, this onus of survival debt may precisely be the only chance women find themselves at the helm of decision-making, and their deftness in managing such debt is why microcredit programs target women, since they register higher repayment rates. The problem of not putting them to overall investment though remains obstinate.

The Case for Resolution / Mapping the Way Forward

Attempts to resolve these problems are as varied as the history of poverty. The last 50 years have seen innumerable campaigns, some even star-studded, in an attempt to garner attention and push for foreign aid. Jeffrey Sachs, one of the leaders in the global crusade to end poverty, has been a strong proponent for foreign aid that would spur investment in poor, low-income countries and set off a chain reaction that would lift households from poverty. However, this has met resistance from anti-aid figures like William Easterly and Dambisa Moyo, who reject the notion of poverty traps and believe that free markets would improve people’s lives. There exists evidence to support both sides, with countries like Rwanda which immensely benefited from foreign aid, but on the other hand, aid represents a very small proportion of funds spent on eradicating poverty; case in point, India.

Microfinance has been hailed as the solution to the poverty-debt cycle around the world and has received much well-deserved praise, including for its pioneer, Nobel Peace Prize laureate Muhammad Yunus. Although, it has been subject to criticism and concerning trends in recent years – the former social enterprise has now seen many large Microfinance Institutions (MFIs) like Compartamos in Mexico and SKS Microfinance in India, which have raised hundreds of millions in IPOs, charging exorbitant rates (earning Yunus’ labelling of them as the new “usurers”). Many other solutions and policy reforms too have been floated including improving access to formal credit and expanding the use of digital and mobile banking services.

But perhaps, the answer lies in simple mechanisms to address the psychology of low-income families by credibly providing them with adequate information. Studies have shown that small investments in information-sharing processes (eg: through outreach programs) and socio-political reforms could allow for inaccurate weak beliefs to be replaced by factual information. This could greatly improve many poverty-related dimensions of their lives.

Merely communicating accurate information about the relation between their investments and spending and their future returns can inform and lead to prudent financial actions – returns on investing in higher education, risks associated with high-interest borrowing, etc. Well-placed and sensible “nudges” can assist poor households in well-judged risk-taking that yield favourable returns like savings and healthcare. Supplying timely information that replaces untenable misconceptions can be the much needed boost that allows low-income households to, once and for all, break free of the vicious cycles that trap them in perpetual poverty and debt.

References:

- Allcott, H., Kim, J., Taubinsky, D., & Zinman, J. (2021): Are High-Interest Loans Predatory?

- Banerjee, A., Breza, E., Duflo, E., & Kinnan, C. (2019): Can Microfinance Unlock a Poverty Trap for Some Entrepreneurs?

- Azim Premji University. (2021, May): State of Working India 2021 – One year of Covid-19. Azim Premji University

- The Journal of Development Studies: The Cost of Empowerment: Multiple Sources of Women’s Debt in Rural India

- The Tribune: Medical debt a major cause of poverty in India

- TheQuint: How COVID Threw India’s Low-Income Households Into Debt Traps

- WIEGO: Gender, Informality and Poverty: A Global Review

Leave A Comment