August, 2021

This article aims to explore how arbitrarily instituted gender hierarchies interact with caste hierarchies. It also seeks to enumerate instances of casteism that play out in our day-to-day interactions with our domestic workers.

5 minutes read

We live in a caste-ridden society. Caste is codified in our structures and determines how we navigate public and private spaces. Further, it dictates which perspectives take centre stage and which ones are pushed to the margins. At one end of the caste spectrum are people whose dominant caste status accords them the ability to live in a “casteless” world, and at the other end are people from caste-affected communities whose lives are defined by socio-economic vulnerabilities. As they do everywhere else, the varied manifestations of Brahmanical patriarchy claw their way into the domestic work industry too.

Paid domestic work is organised along the axes of caste and gender. Structural inequalities within society are reproduced and perpetuated through paid domestic work. This industry is cross-culturally dominated by women hailing from oppressed caste and class backgrounds. According to the National Sample Survey Office (NSSO 2018), the majority of domestic workers in India were female and belonged to scheduled caste and tribe. There are several ramifications of this kind of organisation of work among which are the covert and overt casteist practices that domestic workers are at the receiving end of. This article seeks to explore how arbitrarily instituted gender hierarchies interact with caste hierarchies. It also seeks to enumerate instances of casteism that play out in our day-to-day interactions with our domestic workers.

Historically, women from oppressed caste backgrounds have been subjected to the savarna gaze which naturalizes the purity-pollution standards that stem from Brahminism. The otherisation of domestic workers is thus culturally justified on the basis of casteist notions of hygiene. Their workplace is often a site of discrimination for domestic workers.

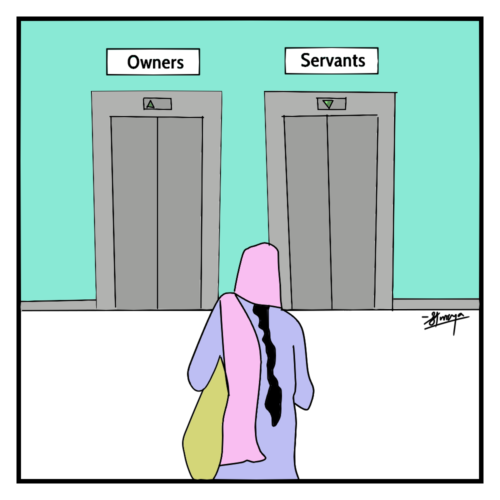

Under the guise of “hygiene”, domestic workers are implicitly ordered to remove their footwear, denied access to the comfort of sofas/couches, provided separate utensils and even denied access to the same washrooms that they are expected to clean. These covert and overt forms of discrimination ensure that the status quo remains intact. Besides, the rigidity of the caste system is such that it does not grant domestic workers the option to change occupations. Their place in the system is maintained through an inter-generational lack of occupational mobility. Domestic workers in India inherit the burden of their caste loci. Added to this are their class and gender constraints.

Under the guise of “hygiene”, domestic workers are implicitly ordered to remove their footwear, denied access to the comfort of sofas/couches, provided separate utensils and even denied access to the same washrooms that they are expected to clean.

The overarching factor that girdles all these discriminatory practices is caste prejudice. Domestic workers are also subjected to intense scrutiny and policing in gated communities wherein they are viewed with suspicion. There have also been several instances of domestic workers being subjected to caste-based sexual harassment by their employers.

The casteist conditioning of dominant caste folks often exhorts them to inadvertently treat their domestic workers in a patronizing manner. Their acts of “goodwill” directed towards their domestic workers – handing over worn-out clothes (that they themselves would not wear) and giving away leftover food so that it does not go to waste – have strong casteist and classist undertones. However, this sort of an attitude has been normalized to a significant extent. Needless to say, it is detrimental to the women employed in the domestic work industry as it demeans their dignity while simultaneously strengthening the saviour complex of their privileged employers.

Women employed in the domestic work industry are discriminated against along the intersections of caste and gender. More often than not, menstruation proves to be a huge ordeal for them as their workplaces are not conducive to their needs. Stigmas attached to their bodies and caste either force them out of their places or work or leave them with no choice but to continue to provide their services in dehumanising conditions.

Stigmas attached to their bodies and caste either force them out of their places or work or leave them with no choice but to continue to provide their services in dehumanising conditions.

Hygienist arguments are explicitly used to deny menstruating domestic workers access to bathrooms. Furthermore, they are seen as “impure”, and by extension, “untouchable” and are hence, vilified. Toilet inequity discourages menstruating domestic workers from showing up at work. Paid leave is a far-fetched notion in the domestic work industry. As a result of this, domestic workers are coerced into slogging through their pain in the absence of regularized pay. Simply put, the right to rest of domestic workers is conveniently glossed over.

Reflecting on one’s privilege and developing a keen sense of empathy are the first few steps towards reversing the savarna gaze and improving the lives of domestic workers. Employers can perhaps begin by generating dialogue with their domestic workers and regarding them as proper employees. They must become more conscious of the fact that seemingly benevolent acts of goodwill (like giving away old clothes or food) have their genesis in the age-old caste system. In the absence of meaningful structural reform to mitigate the inequities in the domestic work industry, it is up to the employers to unlearn the casteist/classist conditioning they have internalised and treat their employees with the dignity that they rightfully deserve. However, individualistic efforts can only do much. Domestic workers are in critical need for better social protection. Therefore, state intervention is mandatory to bring about far-reaching institutionalized change and also thwart oppressive structures.

References:

- ILO: The right to rest for domestic workers, 2015

- Work, Employment and Society: Caste and Gender in the Organisation of Paid Domestic Work in India, 2001

- Feminism In India: Room To Bleed: Do Domestic Workers Have ‘Period Leaves’ Too?, 2020

Leave A Comment