November, 2020

In conversation with Rohena Gera and Tillotama Shome about what it means to cast a domestic worker in the film, “Is love enough? SIR” as a lead in a class-driven society such as ours. We speak about the complex issues of class, privilege, norms, dreams, and desires

6 minutes read

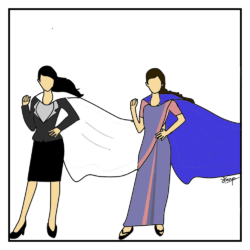

There’s a certain class bias that we operate with- at our homes, workplaces and in the media. In mainstream media, a maid is often depicted from the lens or gaze of the rich family (think Daijaan from Kabhi Khushi Kabhi Gham) or she assumes the role of a seductress, where her character is hyper sexualized (think Japanese comics/manga). Needless to say, SIR-the film is that timely breeze that soothes yet tears gently, subtly- confronting the viewer at the helm of their biases and conscience.

The film is set in Mumbai, beautifully showcasing the juxtaposition of privilege, dreams, and desire. One immediately soaks into the film’s contrasting scenes- that of the informal and formal sectors, of a bad employer and a good one, of quashed dreams and hope, perhaps mirroring our true selves- one that aspires for the better and the other, that pulls us down continuously. SIR is showcased through the eyes of Ratna (played by Tillotama Shome), a domestic help at Ashwin’s (played by Vivek Gomber) place. Ratna is a young, ambitious woman who finds hope in the city of dreams. Ashwin, meanwhile is someone who gave up living his dream of being a writer and upset by his broken engagement, returns to the city of dreams.

The Blue Divide had the opportunity to speak with Rohena Gera, Writer and Director of SIR, and Tillotama Shome. We spoke with them about the elements of the film and what it means to have Ratna as the lead character of a movie in a class-driven society.

We asked Rohena about the choice and the intent behind portraying Ratna as a multi-faceted personality- ambitious, hopeful, diligent, resilient. She shared how it was essential to portray Ratna from Ratna’s own point of view- because traditionally, we’re accustomed to seeing a maid confined by their profession, we don’t see them as a whole, as an individual with multiple elements to their personality. As a viewer, one also sees a sense of dignity that Ratna holds sacred, almost “like her Kryptonite” as Tillotatma shares. What struck us, literally like lightning, was when Tillotama pointed out that dignity is NOT the cultural capital of the rich. And rightly so! As a society, we associate dignity with sophistication and sophistication with a certain socio-economic class, inherently forgetting that one can have all the money and status in the world and yet not be dignified while Ratna echoes dignity at every step.

Rohena also plays along with the idea of happiness- toying with the pursuit of happiness that Ratna works towards a-better, educated future for her sister by being resilient in the face of today’s obstacles. The film also portrays a powerful character, Lakshmi Tai (played by Geetanjali Kulkarni), who is Ratna’s friend. Unlike Ratna, Lakshmi Tai is vocal when her employer shouts at her for slapping the employer’s son but goes back to preparing for the same son’s birthday party with love. It’s interesting to see how Lakshmi Tai looks after the son, “like her own child” while the employer doesn’t view it that way. It’s very rare that an employer and domestic help will be on the same page regarding the work. I, as an employer, inherently may view the Ratna Didi back home as someone who needs to complete tasks in a certain way, without adding much of her element, her unique way of doing work. Is this mildly feudal in nature? Perhaps.

Ashwin’s character is powerful. One immediately starts to take a liking to his character because “he is such a good employer” to Ratna. At the onset, Ashwin isn’t vocal when his father or sister make comments like “You need to be on the heads of these people, else they take you for granted” or speak in a tone that is reflective of the classist society we nurture. He understands what Ratna may be feeling at that point and apologizes later for behavior such as his sister’s. However, as the film progresses, we see Ashwin taking a more active stand against rude behavior when Ratna accidentally drops a glass of wine on a guest.

We asked Rohena and Tillotama whether it was love towards Ratna that made Ashwin more vocal. As a viewer, I assumed that love is what made him an advocate, assuming the role of a protector for Ratna. In Rohena’s opinion, this was a natural progression of Ashwin’s character. She beautifully uses love as a tool to blur the walls of invisibility between Ashwin and Ratna. To her, ‘love is an equalizer’, it’s that powerful force that brings people of varied classes at par. “In life is it okay to shout at someone?”, asks Tillotama. “is it permissible in our society, because we’re extremely class driven? Yes, it’s a sad reality!” . The film calls upon us to question and make a choice, whether we should partake and play a role in that kind of reality. For us to even stir an iota of change, it is imperative to understand that there’s a problem that exists. That shouting at your domestic help because they broke a glass is a problem, that having separate utensils because she is a maid or because she belongs to a certain caste is a problem, that it’s okay to give her the food from three days ago because she is a maid, IS A PROBLEM. Rohena rightly points out that we’re “so unaware of our prejudices that we do not consider that kind of behaviour as inhumane”.

And what happens when we’re spectators of that kind of problem? Does that make us less guilty?

The most sensitive and crucial aspect which the film captures is that of desire, and our biases that engulf it. Tillotama points out, we don’t see people of a certain class to have desires like us. In one of the scenes, Ratna vehemently questions Ashwin why “people like her” cannot dream. Desire to us, is “such a blind spot”, says Tillotama. We often hear statements like “She’s so pretty, but she is a maid!” or “She has such big dreams for a maid”. Doesn’t that tell us something about ourselves? Have we ever questioned, “She’s so ambitious, for a doctor!”. This complex issue of gender, desire and class comes out beautifully in the film.

“The problem arises when you think you’re a nice person and you aspire to be better, but the societal structures are so conflicting”, says Rohena. “I can’t sit at the same table and eat with her, it confuses them, the hierarchy is important to maintain” Rohena mentions that time and again, we come up with such excuses,strengthening our bond with these structures.

We speak about the 1950s segregation, of apartheid in the United States. Rohena questions, how is classist behavior towards people because they are of a certain profession any different? While speaking to them, I felt immediately shaken, made aware of the lies I tell myself “I’m a good person because I gave my maid an old phone for her daughter’s education” , ‘She must be so thankful that I treat her well, being liberal with holidays and whatnot” (Context: My house help barely takes any holidays)

Think about it- do you pat yourself on the back when you offer your friend a glass of water? It’s only humane, right? Why does this ‘humane’ behavior become “God-like” when it comes to dealing the same way with our maids?

Towards the end of the film, it’s refreshing to see Ratna take charge. As she utters Ashwin’s name, Ratna establishes and claims her space, says Rohena. She defies society. Tillotama mentions how this was an act of defiance against these regressive codes of language, class and hierarchy. Our language carries with it prejudices that are so deeply coded. One word has the ability to break down everything that was familiar so far and safe in a class bound society.

The film makes one wonder, if we told stories in which the context of class was represented with greater creativity, what would that mean? To get to that point, we, ourselves, need to accept our bigoted point of view, says Tillotama. And imagine once we did that, we would start to view the world in a whole new way, made aware of our biases, the structures that govern our behavior and the elements that contribute to it. We’d start to feel responsible to take action, to perhaps, for once, view our home’s Ratnas as someone with desire, dreams and hopes.

~

We are thankful to Shruti Didwaniya and Shiladitya Bora for organizing this interview.

Team

- Amiya Shaikh, Illustrator

- Jaagruti Didwania, Interviewer

- Sejal Maheshwari, Author and Interviewer

Leave A Comment