November, 2020

Exploring the various intersections to one’s identity and the barriers experienced by women in the waste and sanitation industry

5 minutes read

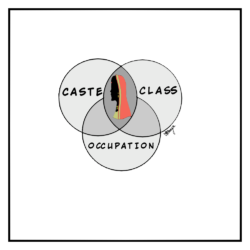

Without the Waste and Sanitation Industry, our cities and states cannot function with the same efficiency that they do. Why is it then, that the service providers who go beyond what’s considered “humane” and clean our filth are deemed inferior? How many of us remember flinching our noses unable to take the stench around a waste dump? Well, about 5 million people in our country actually handle that waste and consequently spend most of their time around waste as part of their jobs. 80% of these workers happen to be women and in Jhansi, 100% of those women belong to the Valmiki community, this community forms a larger cluster of castes that were marginalized since colonial times and brought into urban spaces only to clean them. These gendered and caste-based markers are just some of the many nuances that restrict the women of this sector from availing basic human rights. This further translates into the degree of dignity that they experience with their work. Read on to understand several other layers that define access for the women employed in the Waste and Sanitation industry.

The most common indicator of deprivation and lack of access is the intergenerational nature of occupation in this industry. This largely stems from the caste location of individuals and communities engaged in this work, devoid of reliable upward mobility. Given the work they are engaged in and the caste that they belong to, some sort of dual prejudice exists in the minds of people above them in the hierarchies of caste and class.

They are perceived as dirty or polluted not only because they provide services of picking up our waste but also because they belong to a certain caste. The caste prejudice is often manifested through the trope of seemingly scientific arguments- those of hygiene and food purity. While the prejudice in this regard is deep-rooted, the way it is acted out is quite evident. Several organizations, for instance, Safai Karmachari Andolan work to detach the caste that goes hand in hand with the occupation in an effort to reduce stigma along both lines. As citizens, it is essential for us to acknowledge waste and sanitation workers as service providers and ensure that they are treated with equal, if not more respect. We need to facilitate a life of dignity and pride for them and their labour and humanize their lived realities. Caste-ordained occupation is discrimination and we need to challenge this systemic oppression.

The next important barrier that restricts access in less apparent but more symbolic ways is class visibility. Various factors act as markers of which class one may belong to. These markers are culturally constructed and interpreted. While discrimination in this regard may not play out in the most explicit manners, several cases of “extra” scrutiny in the security checks at metal detectors of shopping malls/corporate buildings solely based on class-based markers do count as discrimination and may translate into discomfort. The ways in which we express the class we belong to by behaving in a certain way with people from lower classes, furthers discrimination and inequality in this regard. These behaviours also include which group gains our sympathies as opposed to those that don’t.

A pressing issue that needs immediate redressal from the State and the larger society as well is the gendered nature of this industry. However, there are several nuances that surround the gendered allocation of jobs in this industry. The argument that gains center stage is the one about differences in muscular strength between men and women. While some reports could affirm this claim, it is interesting to observe that women rarely occupy positions demanding managerial/organizational skills in this industry. These positions are largely occupied by men and that shows how women are restricted to a particular stage of waste and sanitation work. Further, even within this stage, women are seldom given vehicles to drive and hence their radius of work remains restricted or gets covered by the men who are also picking waste in the same vicinity. In this way, women face a lot of competition from men in the job, as well as other women who may be employed as permanent sanitation workers in the Municipal Corporation (which happens to be a meager 8%). As the majority of household work also falls upon women, the work hours that they can dedicate and under what conditions becomes an important question to ask.

Since their work hours may be restricted along with their radius, the amount of wages that they can reap automatically drops.

Gendered disparity not only exists in the workplace but also inside homes. Women who work in the waste and sanitation industry, who may have husbands employed in the same industry and often reported to be under the influence of alcohol to suppress the inhuman demands of their jobs. However, this often gets translated into abuse at home. Some case studies suggest that husbands often extract money from the wife’s income. This furthers how women’s economic independence gets curbed. This is in part due to the multiple roles and responsibilities that they undertake despite systemic devaluation of their effort, their labour.

What is even more alarming is that women workers from the industry have to work without a basic PPE, let alone having facilities that should be provided to address their unique concerns. Several case-studies and reports suggest that the only protective equipment that waste and sanitation workers use is a stick to maneuver the waste which often has glass shards and medical syringes. This is especially pressing in our new COVID-19 influenced circumstances. Some municipal corporations do provide gloves and masks, however, they are known to be less durable. Regardless, the provisions of paid maternity leave and increased restroom stalls to address the concerns of women’s pregnancies and menstruation cycles are indispensable. Further, several women set out to work in the wee hours of the morning which increases their susceptibility to abuse and harassment.

These women are rightful recipients of social and economic security and protection for their relentless essential service. We need to not only acknowledge this, but probe policy intervention in this domain to ensure that these service providers take pride in their job. This can only be possible by creating and investing in an environment with dignified working conditions.

This industry does get recognition at the state and national level, however, the people representing it are again men who have risen to positions of power and challenges that are unique to women and acutely experienced by them, do not reach this pedestal in an authentic manner. Women are merely used as a tool to show numbers but the socio-economic benefits that must also avail of, are largely gatekept by men from the sector.

The lives of women in the waste and sanitation industry are marred with several intersections of caste, class, and gender. Their worldview and aspirations reflect the influence of such intersectional identities. Some of the crucial ways in which we can facilitate our privilege to make space for the representation of these women are enlisted. However, they are not mutually exclusive or exhaustive and merely serve as illustrative prompts for inducting change in this industry:

- Greet and converse with women who are in this sector, who provide their service in your vicinity. Talk to them about their work, their life, hear them out when you can. Express your gratitude

- Get in touch with organizations that work for the capacity building or empowerment of these women/volunteer to teach them or their children

- If your building or household engages in discrimination in terms of having a different route for these workers into the building or different elevators, ensure that you call out this behaviour and take active steps to ensure that it ends

- Read about their working conditions, aspirations and document experiences of the women you speak to and spread the sensitization

Ultimately, it’s important to understand that there are several contradictions in the demands that are furthered within this industry. However, that does not block the apparent ways in which women are always the more vulnerable section of this industry and at an acute disadvantage given the several important gaps in their work. Ensuring that they have their space at work is the least we can do as equal citizens.

References

- Water Aid: The hidden world of sanitation workers, n.d.

- The Wire: The Government has made a welcome shift in sanitation policy that will help develop Indian cities, 2016

- Feminism In India: COVID-19: How casteist is this Pandemic?

- People Groups of India: Balmiki, n.d.

- PRIA: Lived Realities of Women Sanitation Workers in India, 2019

Leave A Comment