November, 2020

Exploring the availability, disparity and implications of data about the formal cigarette manufacturing and informal beedi manufacturing industries

5 minutes read

Disparities in working conditions in an industry for women is not a new phenomenon. Women are usually exploited the most when it comes to the informal sector and the discrimination faced by women in the formal sector is an unfortunately common occurrence as well. What happens when the industry has wide disparities in itself? The Beedi and Cigarette industry is one such example. Through this article, we will look at the scarcity of data available about workers in the manufacturing of cigarettes, the unjust working conditions of the beedi workers and the implications of both. Finally, we will look at some recommendations and suggestions for reforms in both industries, based on the available data.

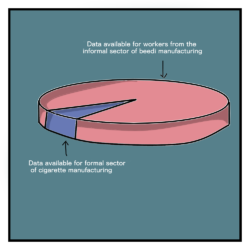

Our initial aim was to study the working conditions in the Beedi and Cigarette industry, and shed light on the difference in the working conditions if there were any. Unfortunately, during our research, we found a lack of data about the workers and working conditions in the formal sector discerning. There is little to no amount of information about the workers employed under the multinational companies that produce cigarettes in India.

While the industry giants are always the first to showcase their employee welfare initiatives to gain some PR leverage, there is no mention of the workers employed in their factories. On the other hand, extensive research has been done in the informal sector of beedi manufacturing. Many reputed organisations have conducted surveys, interviews, and research into the concerning working conditions that beedi makers, usually women and children, are exposed to.

Let’s start with the informal sector. The beedi industry is a Rs. 15,000 crore a year industry in India. It employs about 50 lakh people, out of which almost 90% are women. It is made by rolling tobacco powder in the tendu leaves and then tying it with a thread. The entire process of beedi rolling is manual. The workforce is broadly divided into two categories, the ones working in a factory and the ones working from home. Majority of the workforce is the latter. Studies that have been conducted about the contribution to the manufacturing economy of the country made by the beedi industry on an all India level show that the unorganized sector (at 0.38%) contributes nearly four times more than what the organized sector does (at 0.9%)

Women working from home have to roll a 1,000 beedis in a day to earn about Rs. 120 to Rs. 170. The contractors have a method to underpay them even further, by segregating the rolled beedis into usable and unusable ones. The women are paid for the usable ones, but the contractor would sell the unusable ones in the black market.

These women have to work 10-12 hours a day to roll 1,000 beedis, which is nearly impossible to manage with their daily household chores. So their children are employed to assist them in this task. Hence these women and children inhale tobacco dust all day, (thus increasing the risk of TB, asthma and anaemia) which also causes their fingerprints to fade. All this risk, for a job which underpays them and provides no feasible social security.

For the unregulated informal sector, a lot of research has been done in hopes of bringing government aid and regulation to this highly profitable industry. When that happens is anyone’s guess, but the takeaway from this research material is the fact that data is available. The voices of the exploited workers are being amplified by researchers, social workers, and NGOs. There have been attempts to rehabilitate women to other professions. However, there is no information about the condition of workers employed by the cigarette factories. The lack of information includes the absence of the figures of women employed, and if they are, then at what levels of the organisation are they a part of. That leads us to consider certain possibilities about the condition of workers in the sector.

Firstly, we can work under the scenario that cigarette manufacturing is an entirely automated process and that there is a minimum labour force employed in the factory. In this scenario, we assume that workers are kept to a minimum and that their needs are taken care of due to their limited number. This can be confirmed through foreign cigarette manufacturers who have an automated manufacturing process. However, this level of automation in the beedi industry would lead to large-scale unemployment among the daily wage workers who rely on their underpaid commission to run their household.

Another alternative theory is that the production line isn’t completely automated and the process is mostly, if not entirely, manual. In that case, the lack of data about these workers and their working conditions is a cause of concern. Assuming the implications of this is treading on shaky ground. However, some general recommendations would be:

- to have adequate social security for the workers, keeping in mind the risk of contracting illnesses due to exposure to tobacco dust

- provide adequate wages to the workers based on hours worked and not cigarettes rolled

- make data available as to the existing working conditions to facilitate further research

The lack of data could be one of the reasons why workers in the formal sector are underrepresented in academia. While beedi workers have found representation, there is still a need for government intervention and regulation of workers’ wages in the tobacco industry. Irrespective of whether a tobacco industry worker belongs to the formal sector or the informal sector, they need a certain level of social security and fair wages to sustain themselves adequately.

Through this article, we wanted to draw attention not only to the disparities in working conditions, but also the availability of data for both sectors of the tobacco industry. There is a need to question the lack of data, so as to get more insight into the working conditions of workers in both formal and informal sectors. The availability of data makes a lot of difference with respect to the attention that a topic gets from the academic world, and that has potential to bring about real change in the working conditions of both- the cigarette and Beedi workers.

References

- Livemint: Beedis, wages and the gig economy, 2020

- CGHR: Estimates of the economic contributions of the bidi manufacturing industry in India, 2014

- Pulitzer Center: Fading Fingerprints of Beedi Workers in India, 2020

- Tobacco Free Kids: Tobacco Industry Profile, India, 2010

Leave A Comment