October, 2020

Double-clicking on the glorified concept of work-from-home and uncovering what it means for women in the home-based informal industry of beedi manufacturing

6 minutes read

In the book ‘To Sir, With Love’ I remember reading a line about how you should never bring your work back home with you, as it is said to be a sign of incompetence and lack of planning (contrary to the dedication it would otherwise imply). However, when the world went on lockdown, everyone was forced to bring their work home in the name of competence. Even the essential services brought home some baggage that working in these conditions brought about. Unfortunately, some even no longer had a job that they could bring home. Working hasn’t been the same for anyone in 2020.

While many have written extensively about the migrant labour crisis and covered it responsibly, not enough content highlights how similar working from home gets for people across classes. The migration of labour was not restricted to rural origin populations or blue-collared jobs, as urban white collared job holders too experienced a sort of migration with the imposition of the work from home guidelines. It’s practical for them to move back home with their family and work remotely because as long as there’s internet connectivity, work and meetings could continue irrespective of one’s location. Does living independently no longer hold the same charm and allure that it once did if there’s no bai/didi with the house anymore? It’s practical to move back home (work or no work) because it’s cheaper and easier (and where chores are taken care of), and this should give us a sense of the importance of domestic work. Yet, we brush this notion out of our minds to replace it with some ‘real work’.

Before, work only involved spreadsheets and deliverables; and now it includes bedsheets and delivered food. So how are Indian women coping with this- or is this a change that they learned to cope with a long time ago?

They say we learn history to make sure we don’t repeat the mistakes of the past. The same logic could apply to any subject- we educate ourselves so we could learn to apply it in times of crisis, much like we are in today. Hence, I turned to my notes on organizational psychology to understand why working from home could potentially be the reason we are struggling. I was not surprised to find that the cons outweigh the pros with regard to telecommuting. According to research by Golden in 2006, not more than 2 days a week should be the limit of work from home days in order to maximise both work productivity and job satisfaction. However, all these studies have been in the western context i.e. without considering the other impacts developing nations may have on people who work.

While working from home does come with its benefits, including the time saved on commuting, the work opportunity for people who can’t leave their houses, the increased autonomy, and comfortable environment, the same could be downsides when factoring in the Indian context. No commute time would translate into additional workload with an internal pressure to work more (excessively), more autonomy could create panic and chaos for those not adept at planning, and the environment at home may or may not be the most ‘comfortable’ for households.

Just as we curse the system when we experience any internet connectivity issues, outside our bubble exist houses where electricity and water issues persist year long. Such houses are not a ‘comfortable environment’ for work.

Additionally, it has been observed that telecommuting is easier on men as compared to women and those who have a separate room to work in as compared to those who do not. Again, in India, a much larger group of women are expected to work from home as compared to men on a long term basis even. This might help get things into perspective when thinking of even the white-collar workforce presently. If this has been tough on men it can be concluded that it has been relatively tougher on women. The reason for this could have something to do with lifestyle, personality, or at a larger scale – with the gendered expectation towards women when it comes to housework.

There is also this flawed view that there are no costs associated with working from home. Perhaps the reason people struggle to understand this is due to it being difficult to understand non-monetary costs (like with opportunity costs in economics) as the association of money and cost is so strong. The illustration given below helps visually depict some costs which could translate to monetary costs. High electricity bills with using multiple appliances all day, delivery charges for takeout food, and health-related consequences of such a lifestyle could easily translate into medical bill costs; to name a few. When it comes to medical bills, the beedi workers would have to pay those as well and often cannot even afford it.

Their hands tend to get itchy and reactive to the tobacco, their eyes are strained if they also take up some stitching business on the side to make ends meet, their joints and back hurt due to the position in which they sit for hours on end…and the list goes on.

Whether the costs being paid is physical pain or discomfort or mental strain and stress; there are costs associated with working from home and women across classes are paying them. While people at corporates are experiencing a cut in salary in some instances, people working in the informal sector have never even truly know what fair wages were to notice any cuts. With women workers doing domestic work as well as occupational work, paying additional costs as they do so- is compensation in order or a bigger cut?

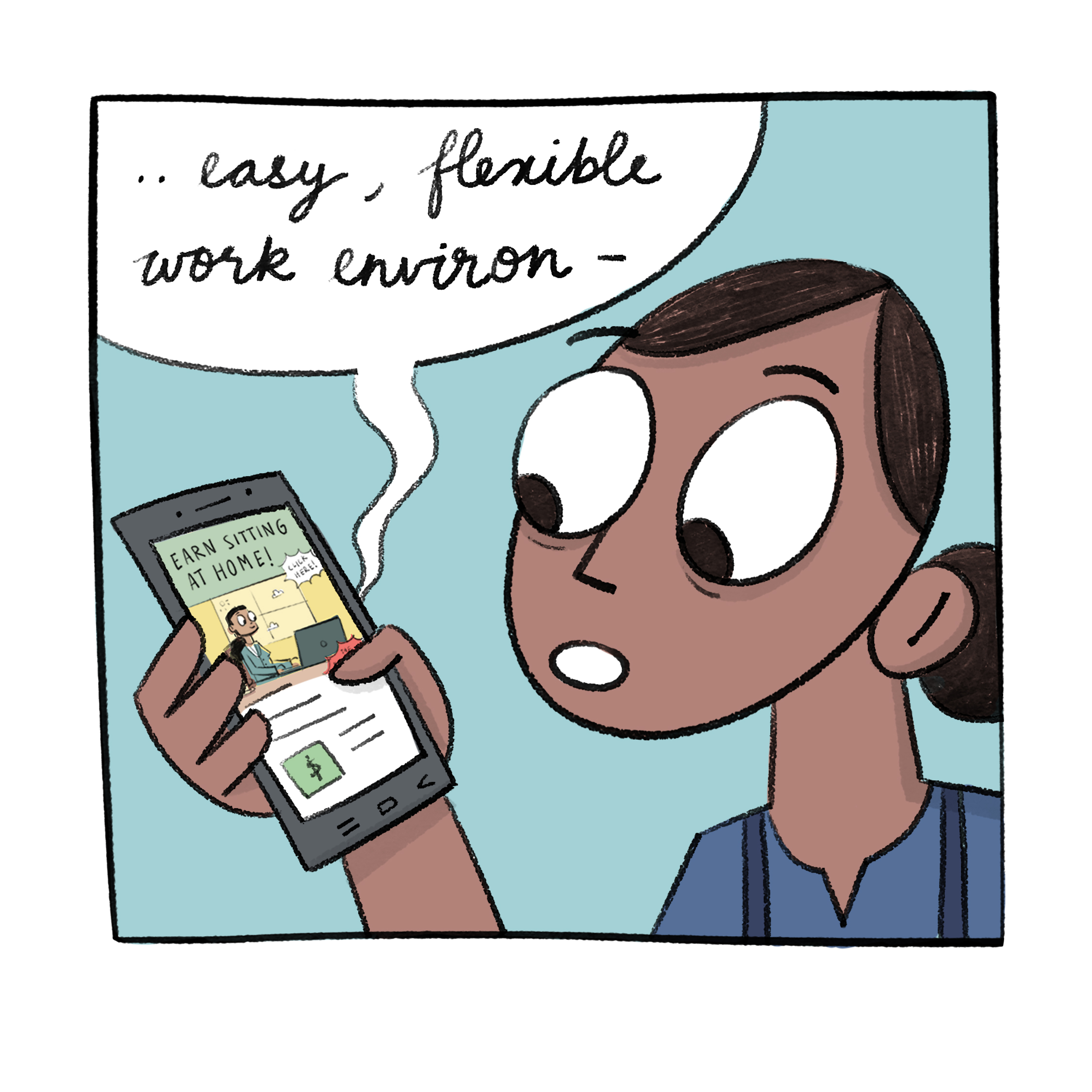

Working from home has its own upsides and downsides, however the present attitudes towards working from home only have downsides. We live in a world where certain subjects (e.g. STEM) are given more respect and preference over humanity related subjects. It’s unfortunate but when it comes to the income levels and why it’s justified to pay people in these fields more one could see why and so we live with it. However, we also live in a world where income levels aside we also attach value and respect when it comes to different types of work. Working from home is said to be easy, and people advertise data entry type of jobs as something that helps women who ‘just sit at home’ earn a quick buck. If you look it up, even today you’ll find advertisements such as the one below-

Amidst the pandemic and still struggling with a work from home situation, people have begun to understand just how ‘easy’ it’s gotten to sit at home to work. Just studying and interning at home has given me a sense of empathy towards women workers who have been in this work situation their whole lives. They’ve been doing this with all the responsibilities sans the multitude of influencer videos on how to get through this with the help of proper planning and of course a facepack and some quick vegan dinner recipes to unwind. If the plight of women workers in the informal sector workers is hard to visualise for the rest of you readers, try to start off by empathizing with the domestic workers and homemakers the working youth of our nation have now turned to for support while they continue to do some ‘real work’.

Our current journey going from hardly working to hard work, is not about the conventional work related to our occupations (be it as a student, homemaker, or breadwinner) anymore. The hard work deals with the changes in mindset and perspective we must inculcate, the focus on mental health and stability to cope with this situation, and a sense of solidarity we must display. This is not even relegated to just women workers, but a commentary on people working at home nationwide. As you read this you may relate to a lot of content, but as you do, also note how you’re in this situation, not only with your colleagues, but also experiencing something for the first time that women home-based workers have throughout their lives. If work from home is not working for you right now, can it work for someone more disadvantaged and in the same cohort as you?

References

- The Hindu: Work from Home in the time of COVID-19, 2020

- Work in the 21st Century: An Introduction to Industrial and Organizational Psychology (6th ed.). Wiley, 2018

- Youth ki Awaaz: This Multi-Crore Industry Is Being Fuelled By Exploiting Tribal Women In Chhattisgarh, 2017

Team

- Preksha Jain, Author and Researcher

- Riti Gupta, Illustrator

- Divya Rodricks, Illustrator

[…] it seem easier, especially because of its “work-from-home” (WFH) nature; which calls for a separate discussion on the understanding of WFH altogether. Moving on, such numbers bring us to consider the extreme occupational hazards that women and other […]