October, 2020

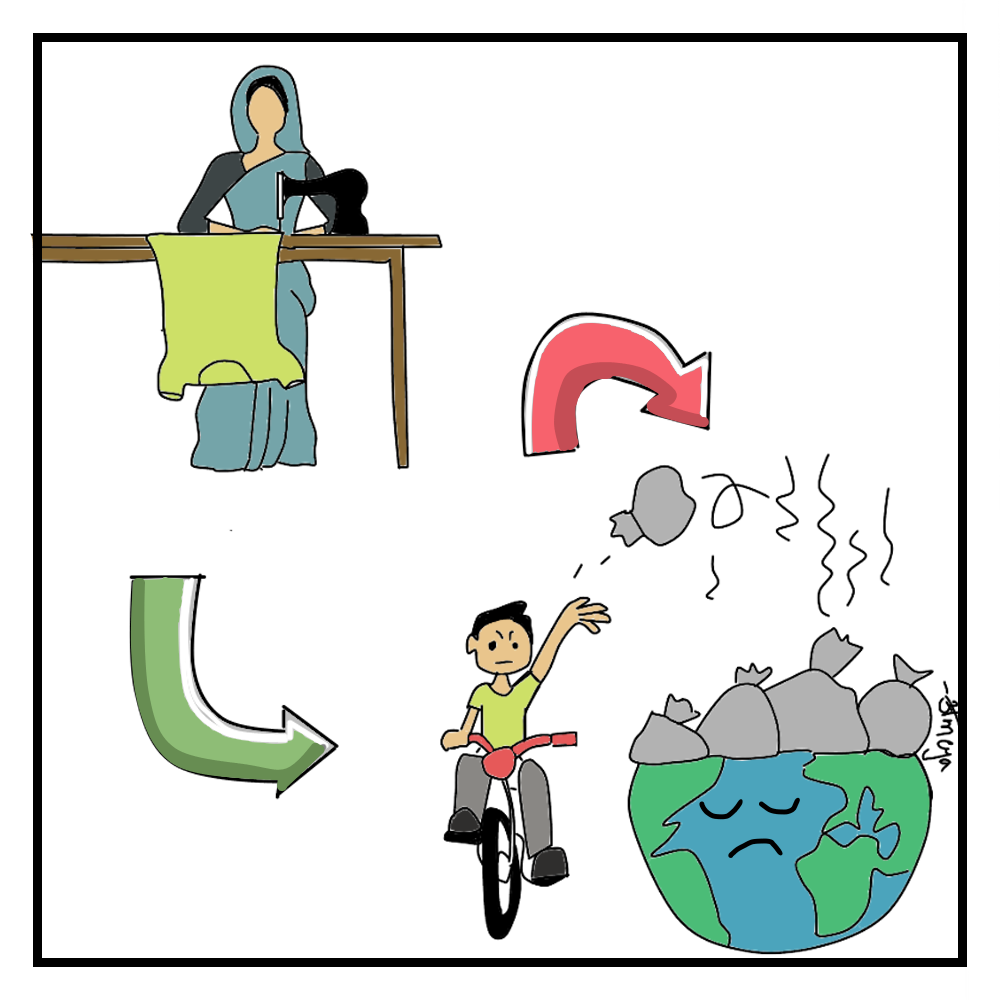

A take on the human costs associated with a concept more infamously known for its environmental impacts

5 minutes read

Imagine this: you see your favourite model walking on the Dior runway, wearing the dress of your dreams. Soon enough, you find out that you can get your hands on a dress that is just as similar – however, at 1/4th the price of the original. What would you do? Most people would grab onto this opportunity and make space in their closets for a new piece of clothing. This is fast-fashion; inexpensive clothing produced at a rapid rate, available to you within no time. Fast fashion helps facilitate the transition of latest styles of clothing – which were previously accessible to people with a certain socio-economic background – to everyone, at ridiculously low prices.

The fast-fashion business model has promoted a culture wherein sales and discounted prices are meant to attract consumers to shop. Despite the environmental and labour costs, most of us can’t seem to get enough of fast-fashion brands like H&M, Zara and so on. Undoubtedly, fast fashion has democratised luxury trends and turned them into a medium of clothing that appeases our desire for novelty.

While fast-fashion makes clothing more affordable, one must not forget the environmental cost that is attached to it. Not only have we started to buy more clothes than ever before, but also have normalised cluttering our closets with clothes that have rarely been used, leading to their treatment as disposable items. According to a report by Greenpeace, to compete in the ongoing race to make and sell clothes that are ever cheaper, the textile industry has relocated to countries with low labour costs and inadequate regulations. What we, as consumers, seem to forget is the fact that today’s trends are tomorrow’s trash. Keeping in mind the high energy that is used to manufacture clothes, “the textile industry is considered one of the most polluting in the world” (Muthu, 2014). On learning about the environmental effects and the work ethic that is perpetuated in the fashion industry, “who made my clothes?” is a question I started to ask myself before making a purchase.

On building women’s agency in the apparel industry

In India, the apparel industry is one of the earliest industries to have developed. Being the second-largest manufacturer and exporter of textiles in the world, the employment opportunities this industry has to offer is unparalleled. According to research published by the United Nations, out of the 8 million people employed in this sector, more than half of them are women (Russel, 2020). Hence, the female narrative as a part of this industry is pertinent to understanding fast fashion.

Women’s economic empowerment is multifaceted and, as identified by International Center for Research on Women’s (ICRW) eight building blocks framework, requires the convergence of economic and non-economic factors, including safety, freedom from violence, and the opportunity to be heard at work and in society (Reller, 2014). According to the Business for Social Responsibility (BSR) report, for several women workers in India, a job in the apparel sector can be a first step into the formal economy. This, in turn, is an essential stride for women to reach financial independence and the start of a path out of poverty. When it comes to building women’s agency, research indicates that garment work, as a sector that employs significant numbers of women, has an impact by delaying marriage, reducing the number of children women have, increasing education, and increasing women’s decision-making powers at home and in the community (Heath and Mushfiq, 2015). In an otherwise patriarchal society, women are now starting to be seen as economic contributors in their families – which is a stepping stone on a path that leads towards gender equality in our country.

Is this ethically sound?

Although the fast fashion industry amplifies work opportunities, one needs to evaluate the negatives. The idea of consumers getting comfortable with products at throwaway prices, without evaluating the consequences of an industry that may be exploitative in nature is something each of us should consider. Before we applaud fast-fashion mega-giants like H&M & Zara, we need to take a minute to question the ethics of such brands.

Within various garment industries in India, women garment workers are often the primary earners and caretakers for their families. However, there have been a number of adversities reported over the years – the families of women garment workers suffer when long working hours are enforced upon the garment workers. If they refuse to comply, they are often terminated without any due process. Callous production targets, hazardous working conditions, wage theft have also been long-standing tribulations that women workers have had to face.

In an interview with Open Society Foundations, Asia Floor Wage Alliance’s Anannya Bhattacharjee expressed the grievances that these women workers in the garment industry have had to face. She claimed that most workers do not get paid sick leave, and women workers are often denied maternity leave and access to childcare. Women workers also face gender-based violence in the workplace, including being forced to provide sexual favours. It is almost the norm in various places.

Moreover, women and girls tend to constitute a majority of home-based work across numerous informal sectors, along with the exploitative conditions that come with them, which in turn perpetuates the subordinated and oppressed status of women and girls. As per ‘Tainted Garments’, a study conducted by Siddharth Kara on the exploitation of women and girls in India’s home-based garment sector, he posited that due to the lack of transparency and the informal nature of home-based work, wages are almost always suppressed, conditions can be harsh and hazardous, and the worker has virtually no avenue to seek redress for abusive or unfair conditions.

In addition to this, the research findings suggested that 99.2% of workers toiled in conditions of forced labour under Indian law, which means they do not receive the state-stipulated minimum wage. In fact, most workers received between 50% and 90% less than the state- stipulated minimum wages (Kara, 2019). By the same token, The Wire reported how in Karnataka, garment workers get paid a minimum wage of around Rs. 8,000 a month – 25% below the urban poverty line of Rs. 10,800 a month, based on the Rangarajan Committee report (Nathan, 2019). This goes to show the conditions in which labour is exploited in our country, leading to unfair wages and a poor work-life balance for women workers in the garment industry. The ‘discounts’ offered by brands are enabled by the low wages that are given to workers in the apparel industry – thus, making it possible for us to get a hold of clothes at seemingly low prices while brands maintain their profit margins.

How can we help?

The barriers to women’s empowerment in India appear to be systemic. Keeping this in mind, it is essential for the apparel sector to influence and encourage policy change. Journalist and author Elizabeth L. Cline stated how the voices of suppliers and workers must be at the center of all decision-making processes. The impact of policies that are proven to advance women’s empowerment will directly benefit women labourers in the garment industry. As per a Business for Social Responsibility (BSR) report, these policies can address challenges such as equity in property ownership, access to education and healthcare, protection from violence, worker rights, and equal pay for equal work. Together, the apparel sector can influence policymakers and advocate for change as well as enable other actors, such as NGOs, suppliers, and partners, to take action and accelerate progress.

We need to hold brands accountable when issues regarding worker safety and worker rights come to the forefront. The #PayUp campaign that has taken social-networking sites by storm is a prime example of people holding brands accountable for conducting unethical business. Similarly, there are several organisations that have been rallying for the ethical treatment of women workers in the garment industry. One such organisation is The Garment Worker Diaries wherein their objective is to collate credible data on the work hours, income, expenses, and financial tool use of workers in the global apparel industry, in order to develop government policies as well as factory and brand initiatives related to improving the lives of garment workers. By the same token, Fashion Revolution India is an advocate for transparent and ethical fashion in India. Their aim is to ensure that measures are being taken with the intention of furthering the lives of workers in the apparel industry.

British fashion designer Vivienne Westwood once said, “buy less, choose well and make it last”. It is time for us to become conscious consumers: we need to reflect on the items we purchase, keeping in mind the environmental and social impact that our purchases have. Moreover, it is imperative that we lean towards sustainability – for we must learn to give our clothes a second life, until we can say good-bye to them. Sustainability is not just about the survival of the planet, but of the kind of people living in it.

We, as consumers, must join the revolution that challenges the fast-fashion industry to provide fair wages, safe workspaces and be transparent in their dealings.

Empowerment does not take place overnight – the process is slow, with systemic and structural changes that are to be made with time. It is time for companies to demonstrate a commitment to provide women workers with safer working spaces, policies to further their economic and social growth, equal pay and so on. The rules, and the system itself, need to be re-written in order to empower women workers with equitable opportunities in the apparel industry.

References

- Quartz: Factory workers for major fashion labels live confined by guards, 2016

- ILO Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 62. Geneva: What does the minimum wage do in developing countries? A review of studies and methodologies, 2016.

- Vogue: The fast-fashion system is broken—so what happens next?, 2020

- Fashion Revolution: Exploitation or emancipation? Women workers in the garment industry, 2015

- Greenpeace: Timeout For Fast Fashion, n.d.

- Tainted Garments: The exploitation of women and girls in India’s home-based garment sector, 2019

- McKinsey & Company: How India’s Ascent Could Change The Fashion Industry, 2019

- BSR: Empowering Female Workers in the Apparel Industry, 2017

- The Wire: Protesting Exploitation, Women Workers From Garment Industry Paint Bangalore Red, 2019

- Niti Aayog: Weaving The Way For Indian Textile Industry, 2020

- Worker Diaries: A Look Inside a Garment Worker’s Household, 2020

- Open Society Foundations: Q&A | Women Workers in Fast Fashion Demand Justice, 2020

- New York Times: Made for Next to Nothing. Worn by You?, 2019

- Ethical Trading Initiative: I can do anything | Empowering women in India’s garment sector, 2018

- The Guardian: Major western brands pay Indian garment workers 11p an hour, 2019

- The Women Behind The Clothes: Worker Health And Well-Being In The Indian Apparel Sector, 2020

- Feminism In India: The Dark Side Of Fast Fashion Your Favourite Brands Are Hiding, 2018

- Medium.com: Fast Fashion: Our Cheap Clothing Addiction is Doing More Harm than Good, 2017

Leave A Comment