September, 2020

An understanding of the discrimination and hierarchical treatment that workers from the waste and sanitation industry face by virtue of their profession

5 minutes read

How many times have we found ourselves cringing or holding up our noses when we passed by a garbage truck? It’s natural, isn’t it? The stench, the foul smells. For a moment, let’s introspect and try to understand how these reactions may impact someone who actually engages with this waste as part of their profession. Day in and day out. Someone, who not only works here but most often, single-handedly takes care of household responsibilities as well.

This piece attempts to serve as a call for action to understand the discrimination faced by workers from the Waste and Sanitation industry. While men and women alike face a ton of struggles, women are doubly stressed. Read on to understand ways in which we can sensitize ourselves and possibly help in ensuring that their workplace is a safer space than what it is right now, especially for the woman worker.

The Waste and Sanitation industry apart from being fraught with a not so invisible caste history, has an inherent stigma attached because of the product that the industry is engaged with. This stigma is furthered and is also attached to people who toil hard to ensure that the waste from our homes, housing societies, colonies, and ‘cities’ is well disposed of.

Why is it that waste, that each of us inadvertently produces, comes to influence the attitudes with which we view ‘waste work’ and waste workers?

On some introspection, I have realized that a lot of our reactions are what we have learned and have been actively taught. Reactions like making a face and holding our breath might have natural bases while walking past a mound of garbage. However, when these reactions are actively expressed by some of us when the workers who deal with the waste walk past us have several far-reaching consequences, which we believe can be avoided to a certain extent.

There have been instances where shopkeepers have poured water and washed off the very stairs that were swept by these workers, simply because they sat there a little while to catch some breath. There are instances documented in ‘India Untouched’, a documentary, where some primary school girls are made to clean the washrooms of their schools simply because they belong to a family that is involved in the work of dealing with waste. The inherent (and unjustified) stigma attached to this work and its workers gets deeper still and affects the dignity that workers themselves feel towards their work. Several inhuman instances have come into light in COVID-19 times like having separate elevators for workers as opposed to residents. This clearly highlights the inherent discrimination that several ‘educated’ people have also engaged in. It goes on to convey that with or without their work, whether or not they are working while commuting to their place of work, they are different and will be treated so. The fact that they are perceived as inherently dirty and impure has never been clearer than in these times where everybody is desperately looking to solidify the remnants of their social security.

How is this problem more acute for women?

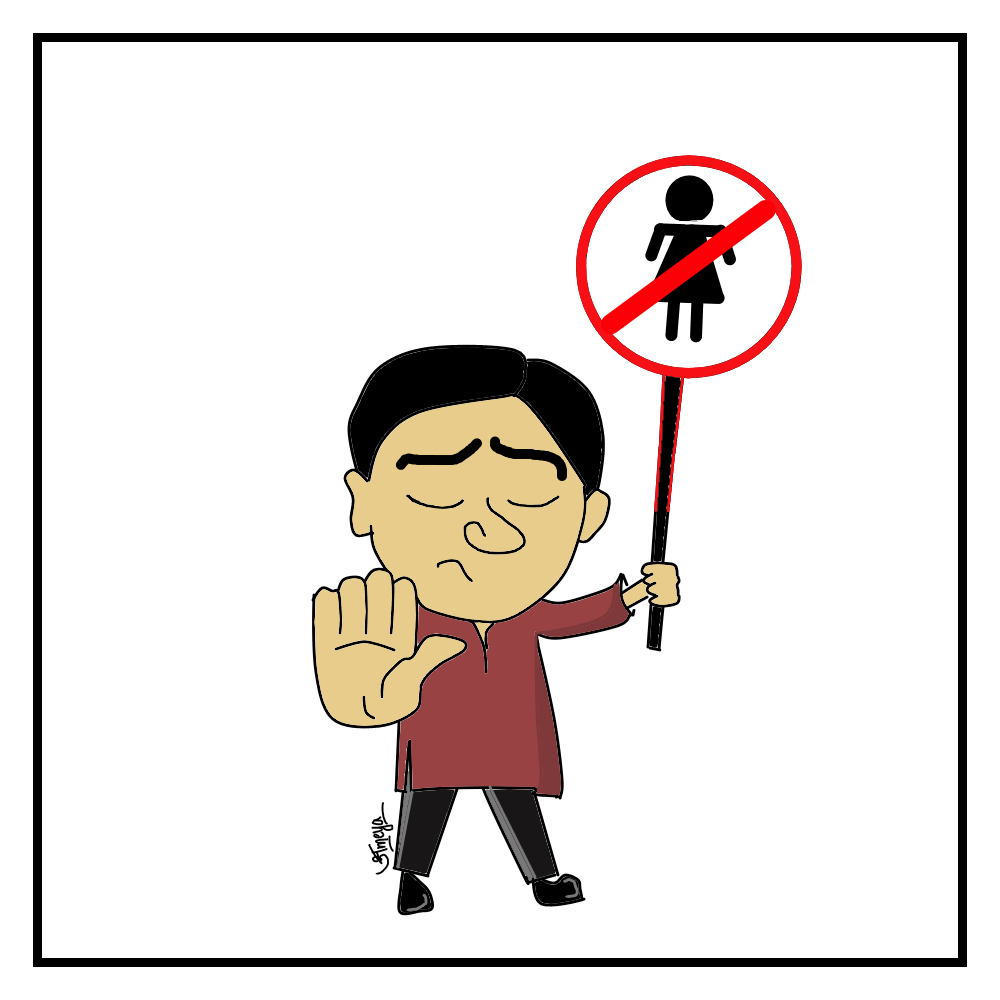

The main argument that is widely stated and accepted, is that women have relatively less physical strength as compared to men. This shows in their exclusion from several employment opportunities, some of which are outright discriminatory. One such opportunity that had been kept away from women for a long time, is that of assigning them to vehicles that pick up waste. Most drivers of such vehicles are men. However, in the tie-up with Pune Municipal Corporation, SWaCH facilitated access to vehicular collection of waste for its women stakeholders. This access takes women a step ahead and expands their radius of waste collection. The effort is not only commendable but pathbreaking. This intervention is a good example of successful collaborations between Municipal Corporations and Civil Society organizations.

The other kind of discrimination (among many others) that we’d like to draw your attention to is the inferiority with which these women are treated in their own homes. Women are often responsible for taking care of household chores and primary responsibilities as well, so the amount of time that they have to themselves is very limited. Besides, the income that they work so hard for, is seldom left for them to use the way they want to. Husbands, children, and other members of the family often cash onto the income that women bring into the house because there is an understanding that the money brought by the woman is for the entire house. This understanding is not present for the income generated by men and thus becomes an inequality that we need to address.

Further, women in the Waste and Sanitation industry whose husbands might be engaged in the same industry have to work in more adverse conditions. These include entering man-holes and cleaning the drainage collected with barely any PPE.

To suppress the extreme inhumanity of this act, male workers often resort to intoxication in the form of alcohol or local drugs when engaged in their work. Naturally, when they develop an addiction, financial regulation becomes a bigger problem with the limited income that they generate. What does this mean for women? Well, men begin exploiting their wives’ income in order to pay for these substances, either out of addiction or because their job is so frequent. In that sense, women are often left to fend for themselves with no real claim or security on the money that they earn. This threatens the economic independence of women and indirectly perpetuates the vicious cycle of poverty. Naturally, this pattern needs serious intervention to uproot other deeply entrenched issues.

The way of dealing with discrimination also involves starting work in the wee hours of the day so that other members of the community don’t ‘find out’ about their work. Such are the consequences of the long-attached stigma. Working in the dark often renders women workers susceptible to abuse and harassment, another community concern that all of us need to be responsible for. In order to end this cycle of occupation, workers from this industry lay emphasis on education but often invest in the education of the sons of the family, while simultaneously stressing and straining to earn enough to get their daughters married and ‘settled’. While this is a fair approach to have in a society where girls and their education is not given as much importance, we believe some work is required right from primary schooling to ensure equal treatment of boys and girls in the classroom as well as in the environment of the home.

How can we then change the seemingly trivial things that might be understood as a divide in the amount of dignity you have v/s how much a worker dealing with waste might have? The voice of caution that we have been able to identify is- avoid such reactions as much as possible. Simple things like a smile of gratitude can go a long way to reduce the stigma that has long been attached to this extremely fundamental and difficult field of work. We need to start questioning ourselves when we visibly distance ourselves/our children while walking past a worker engaged in the work of waste and sanitation. Endeavors like Adult Literacy Programmes for upskilling etc. can be designed according to the convenience of these women. Change may begin small, but the gravity of small acts goes a long way. If it has worked to create and establish stigma around this industry and its workers, it might also play a significant role in ensuring the dignity to their labour, that we have closely kept away from them for so long.

References

- SWaCH: History of SWaCH, n.d.

- Feminism In India: COVID-19 Lockdown: Domestic Workers and a Class-Caste Divide, 2020Biswajit Rath: India Untouched: Stories of a People Apart, 2019

- PRIA: Lived Realities of Women Sanitation Workers in India, 2019

- Human Rights Watch: Cleaning Human Waste, 2014

Leave A Comment