August, 2020

An analytical and informative read on how COVID-19 impacted the informal workers in two manufacturing industries

8 minutes read

‘Tis the season of Spring! Birds chirping, flowers blooming, nature unveiling its brightest hues. Beach bodies, graduation trips, summer vacays, shopping sprees, parties, exams, and work-life. Life isn’t perfect, but still regular. Then an invisible piece of biomolecules, which can’t even survive on its own, wreaked havoc in a small corner of the world and reached our doorstep. As scientists and governments were decoding it, people started to fall sick at the drop of a hat. They said it’s highly contagious. They said, there’s no cure for it. Things changed overnight when a complete lockdown was announced.

No one was allowed to move out and people started to crib over how they miss their regular life. While a section of the society gradually made peace with the situation, posting ‘lockdown stories’ on social media, for the other less fortunate section, their problems had just begun. Food crisis, migration, loss of income, greater vulnerability to the disease, mental health issues, exploitation, domestic violence… the list goes on. We call this section the ‘informal workforce’ while throwing jargons in discussions, but often fail to take cognizance of how deep-rooted their problems have become amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Unfortunately, another section within this informal workforce which we tend to overlook is the women workers.

Women And Clothes – An inexplicable bond

For reasons best known, the garment sector has always been associated with women. The industry, in fact, is the second biggest employer of women workforce in India. They work as both formal employees at the factories, and informal employees at their homes on a piecemeal basis, which means that they get paid for every piece they stitch and work on. This kind of contract labour is widespread in India, mainly in the export sector.

Since time immemorial, women have predominantly assumed the role of caregivers. This led to the emergence of certain gender-based norms that over time have restricted their contribution to doing all the housework and taking care of the family, all by themselves. Their capabilities and wishes to work outside the house have been largely undermined. In such a case, how is the garment industry able to employ women at such a large scale? It, in fact, thrives on their participation.

Women workers in factories are usually brought on board through community mobilization and training. When any unit is set up in villages, the administration goes around spreading the word about it and inviting the women folk to come, get trained, and earn. The offer is luring enough and requires skills that most women would know already. Many of them are not highly educated, with primary school being the highest level at which they would have studied. The job provides not only a stable source of income, but also financial independence and empowerment. Every penny in a poor household counts. When the factories are city-based, a lot of women also travel long distances from their villages for work. In such a case, where community mobilization and training cannot happen, it is through references to the existing employees that new employees are hired. A trend can also be seen in women seeking employment in the same factories where other women of the village work. Women manage all this alongside other household chores like tending to livestock, working on their agricultural land, fetching water, cooking, and cleaning.

The factories are both big and small scale. Business comes from global brands that outsource their work to these factories in developing countries like India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Africa, and others. Thus, exports are a major chunk of revenue earned.

A significant feature of the industry is the high attrition rate. The workers are contractual labourers and migrants, and unfortunately, a job is the last in the priority list of these women, who are always too occupied with household chores and taking care of the family. In the eventuality of an idiosyncratic shock, for instance, an illness of a family member, women would be the first to leave the job.

COVID and Lockdown- a double whammy?

People were forced to stay at home, and allowed to come out only for necessities. Clothes did not make it to this list of essentials.

With the coronavirus epidemic hitting the world at an unprecedented rate, exports and trade took a low hit. For the fear of the spread of the virus, and as a precautionary measure, many nations stopped international trade early on. This meant a supply chain shock for the garment industry. Complete lockdowns were imposed in countries, especially in India, and social distancing emerged as a remedy, People were forced to stay at home, and allowed to come out only for necessities. Clothes did not make it to this list of essentials. Brands were quick to anticipate the resulting lack of business amid the fear of the disease, and the ensuing lack of trust. Stay-at-home was the new mantra. Thus, new orders were stopped and many existing ones rolled back. Needless to say, the industry crippled not just in India, but globally as well. The Brick and mortar stores saw a decline of up to 60% sales in March. Apart from them, online retail suffered too. The sales of fashion brands fell by 15% online by March. To compensate for the losses, factories had to lay off workers. The effects were more pronounced for small factories. In June, a garment unit in Karnataka laid off 1200 workers without notice. Likewise, many other small factories have had to completely shut shop, with little chances of them resuming or reviving.

The lockdown in India brought with it the migrant crisis. The women who worked in the factories started to return to their villages. Unfortunately, even post the resumption of activity, the ones who left their jobs may not be able to get them back as the industry is expected to remain out of business for the coming months.

Another major challenge that workers faced was wage loss. The wages are calculated on a per-day basis and the payments are made at the end of the month. Because of the lockdown and the losses, wages were either cut to half or were not paid altogether. They, the women, lost their primary and only source of income.

The trickle-down effect

Indian economy suffered a blow owing to the pandemic and strict lockdown. Private investment is the stick that can pull it out of the quagmire. For this, however, a fertile ground is needed which encourages private investments. Stringent labour laws, that were considered a hindrance for the same, were amended and accepted by most states in India. A significant change being the increase in working hours from 8 hours to 10 hours a day.

These amended labour laws, if implemented by the factories, would have a direct bearing on the female participation in the workforce. Such long working hours are infeasible for women workers who are already straddled with family and household chores, and other expectations. It is all the more difficult for them when their children are young. The difficulty increases as children are home throughout the day and with schools being shut, keeping them occupied becomes another task in itself. Husbands also do not partake in sharing this load typically either. While one may anticipate that the factories will come to a standstill if women leave their jobs, there is also a catch here.

The women may not have any other alternative source of income, predominantly because their educational qualifications are low. They would either have to take up work as domestic help, or be forced to make peace with these norms and continue working. It’s a dilemma between taking care of their family, sacrificing their family time, or increasing the stress of juggling both family and work. According to a survey conducted by the UN Women’s Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific in developing countries (such as Bangladesh, Cambodia, Philippines, Maldives, Pakistan and Thailand), women are more likely to face reduced working hours, increased rate of stress and a reduced medical insurance cover post the Coronavirus pandemic.

One may assume that women workers would have a higher bargaining power, owing to their enormous contribution to the workforce. Yet, this does not seem to be the case. It could be attributed to the fact that these workers are replaceable, and the job monotonous. The factory supervisors could be extremely harsh and unforgiving. You either survive it all or leave. However, this attitude is glorified in certain high paying mainstream jobs but is a bitter pill to swallow in the informal industry. Moreover, most of the workers have been trained by the very factories they work in. What bargaining power are the women left with then?

But the Unlocking will make things better..won’t it?

The factories have started to function again, albeit at a reduced capacity. This is a step up from no work at all. Social distancing has to be maintained as per the government guidelines. However, it is unlikely still, that the woes of the women workers will vanish.

A disturbing trend that has been seen in Karnataka on revival of the factories post ease of lockdown restrictions, is the closing of creches by the factories. This could be due to the lack of funds and resources to run the creches. One could also claim that it is to maintain the safety of the young children that fall in the vulnerable group of the disease. However, it is difficult to ignore that because of the closing of these creches, many women will be forced to leave their jobs. Many of these women already do not have a chance to return. Under the Indian labour laws, it is compulsory to provide creches in factories with more than 30 women employees. The decision to not reopen them can be contested as illegal. One could also argue that this is a convenient way to reduce the workforce without having to formally lay them off.

When the women return to work, they would have a shift of 10 hours if the new labour laws are implemented. This in turn will also affect their teenage daughters who will be forced to take care of the family in the absence of her mother. This is because of the mentality, “if not the girl, then who?!” In such a scenario, the drop-out rates from schools for girls is expected to increase. Here’s another glaring issue of gender bias staring right into our eyes- girls’ education is taking a backseat in order to fulfill their gender-stereotyped responsibility of a ‘nurturer’; “After all, that’s what she has to do all her life.”

Let’s Meet Rashmi

Rashmi now manages four jobs in a day- the electrical shop in the daytime, taking tuitions for young children in the evening, and sewing work at night, along with managing her household work.

Rashmi is a small-time tailor, hailing from Bihar and has been living with her husband and three children in a small rented accommodation in Chandigarh. She learned sewing at a small sewing center run in her village which is supported by a local women’s volunteer organisation. Her sewing machine is her best friend, with which she stitches beautiful clothes and manages to earn an extra buck to support her family. When COVID hit, her life went for a toss – orders dried up as people were wary of going to local tailors who worked from home. There was paranoia regarding the virus and the places where it could be holed up. Customers did not want to venture out of their homes. Moreover, the cloth pieces they gave for stitching could get contaminated as well, by coming in contact with the tailors and their sewing machines. They were ready to wait until things got back to normal to get new clothes stitched. Better still, it was more reliable to order clothes online, without having to really step out of the safe confines of their homes. Since offices were shut, and other social gatherings prohibited, nobody really felt the need to buy and stock up new clothes any longer. Things were so bad in the month of April, that her income from sewing became nil.

To add to her problems was the mounting rent of her house. Although her landlords were considerate enough to forego the house rent for a month, it had to be paid the next month. The children’s education suffered too. The private school in which her 6-year-old son studies, decided to go digital, and send the day’s lessons to parents on WhatsApp. Page numbers from the books were marked and sent to parents, and the children had to learn that. But this required them to invest in books that cost at least Rs. 300 each. With no source of income, it was difficult to make that investment. Being migrants from Bihar, in the absence of a ration card, the government schemes for food couldn’t be availed either. Savings would be used up in feeding the family.

This went on for about 2 months, until last month when Rashmi landed up a job in an electrical shop. She does a variety of work from soldering, to stock keeping, to anything that she comes across and is required of her. The income stabilised this month, but Rashmi was working overtime to achieve that. Stitching orders started coming in too. Rashmi now manages four jobs in a day- the electrical shop in the daytime, taking tuitions for young children in the evening, and sewing work at night, along with managing her household work. A typical example of portfolio diversification, to combat a shock by a household. When she’s out for work, the worry of her young children alone at home keeps gnawing at her. Yet, she keeps working to keep her family afloat. While we could see a story of strength and resilience in the face of adversity, we could also see how ‘empowerment’ could be what we tell ourselves to cloak a failure of the system in aiding her appropriately.

The Beedi Workers Aren’t Immune Either

The Beedi industry employs women in home-based work primarily. According to a research study undertaken by AF Development Care, 96% of the total beedi workers are home-based workers and the remaining 4% are employed with factories. About 80% of the home-based workers live in rural areas. West Bengal, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka have the highest proportion of women workers. Unfortunately, the home-based industry is also a hub of child labour, where children work before and after school hours and for almost 12 hours on weekends. A study by the Voluntary Health Association of India, conducted in Murshidabad and Anand shows that the industry blatantly flouts labour laws, with 76% of the workers getting paid only Rs. 33 for rolling 1000 beedis. This takes almost 12 hours or more, per day.

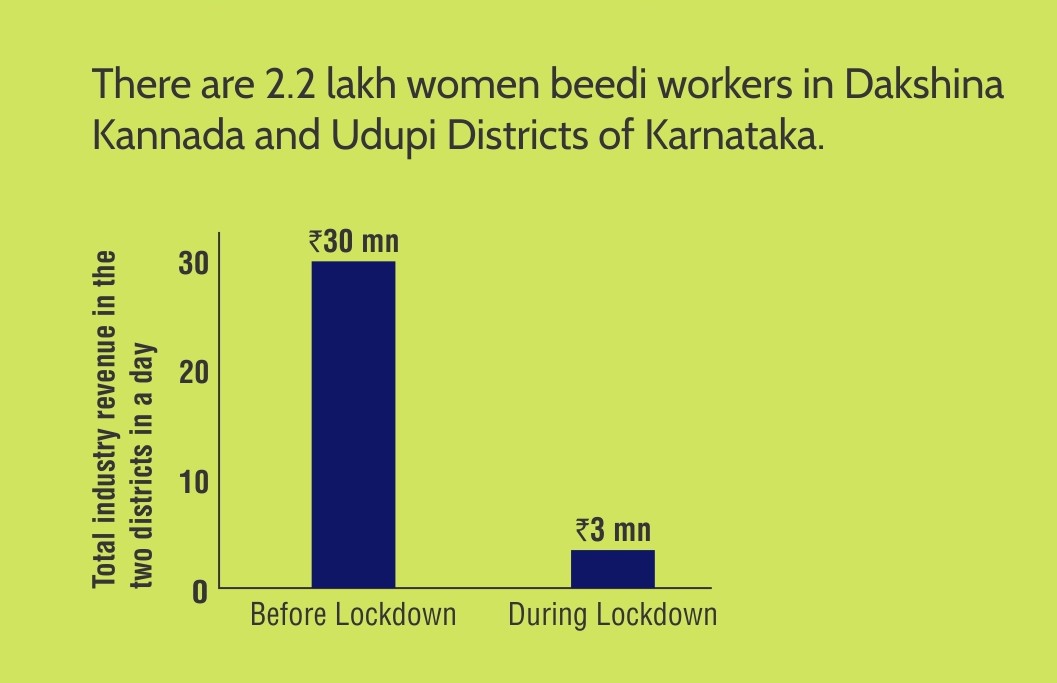

Their lives were already in drudgery, reeling under health hazards caused by rolling beedis and abject poverty, when COVID hit. When the lockdowns were imposed, the Beedi industry suffered a major shock. In Karnataka, the average pay of a beedi roller is Rs. 150 per day for rolling 800-1000 beedis. Dakshina Kannada and Udupi employ 2.2 lakh women workers as beedi rollers (2020). This makes up around Rs. 3.3 crore of earning per day. The workers lost a revenue of Rs.180 crore in 60 days of the lockdown period.

The problems are manifold. As the majority workforce is informal, government relief packages could not cover them. Nor were any special packages announced to provide income security to these informal workers. Many had to depend on government ration and cooked meals for food.

The raw material for the industry is tendu leaves, which are sourced from Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan. These are the states which were also severely impacted by COVID and interstate transportation had been stopped. Neither could the beedis be sold to other states, nor could it be exported. Thus, production came to a standstill, and wages were not given.

What Next?

It is important to bring the informal workers under the ambit of social security nets. NGOs and other volunteer-based organisations are indispensable in this regard. However, civil society as a whole must join hands and help alleviate the situation. The One Nation, One Ration Card scheme is (hopefully) a step in the right direction towards providing food security to poor families, irrespective of their State of origin. Although it may be difficult to bring everyone in the formal sector, attempts need to be made to reach out to all workers and address their needs. Livelihood interventions may be required at a lot of places, with the promotion of SHGs and collectives remaining at the forefront to provide better representation and power to the workers.

Pro-women policies will have to be made with concerted efforts. Especially in cases of hazardous professions like beedi making, the focus must shift to providing women with alternate livelihood opportunities that are more sustainable, economically remunerative, and safer.

Skill-building of women, primarily employed in the beedi industry, should be carried out, keeping in mind the local context and capacities. A leaf can be taken out from successful efforts made by southern states like Tamil Nadu and Karnataka.

The impacts are slowly unfolding, and right now what is most important is to not take these women workers for granted. It is only when they are given a voice, can policies be framed and relief be provided.

References

- Deccan Chronicle: 2.2 lakh beedi rollers left reeling by coronavirus lockdown, 2020

- The Economic Times: After retail stores, fashion brands’ online sales drop, too, 2020

- The Print: Fewer working hours, higher stress, drop in income: UN survey shows how Covid affected women, 2020

- Business Insider: New study reveals the state of women beedi rollers in India, 2020

- Scroll.in: In India, women garment workers are being forced to leave their jobs because of this one reason, 2020

- The New Indian Express: Garment company lays off 1,200 workers in Srirangapatna, 2020

- Hindustan Times: Bidi workers slave it out, for nothing, 2004

Very interesting and informative read. Crisp and well written. Look forward to more articles from you

Very well written dear….. 👍🏻👍🏻👍🏻👍🏻

Very good read, great work, would like to read more